Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.

(America never was America to me.)

This is how Langston Hughes begins his poem Let America Be America Again. I teach this poem at least twice a year in my classes- once to study form and again for a unit on cultural identity. In many ways, it’s my attempt of explaining to students the duality of the “Black America”: a country which offers a dream of riches and wealth while also historically slamming its knee down on their throat. This is a country of cliff-side extremes, feasts and famine. Certainly some of us knew that the “La La Land/Moonlight” flub from over a year ago would serve as a classic example of how the black community can celebrate while simultaneously shaking their heads.

Yes. We can lose a Kanye and gain a Gambino within a span of a week. And so it goes.

I am reminded of the Hughes poem when I watch Gambino’s now buzz-worthy video for “This is America”- his newest track from his upcoming, and possibly final, LP (at least in his current moniker). Childish Gambino (aka Donald Glover) jumped on my radar back with his debut studio album Camp (2011). From there, Gambino has had to establish himself from just another “celebrity doing music” to just a certified star. His hit FX show Atlanta has allowed him to flaunt his acting/writing/directing chops while his 2016 LP Awaken, My Love made him a household name in popular culture.

While his other single “Saturday” sounds a bit too close to the Gambino that has nothing to say (though with a wit to say nothing at all), “This is America” works in tandem with the video to deliver what is Childish Gambino’s most poignant and political commentary on the state of our country.

Shot by Hiro Murai (who collabs with Glover on Atlanta), the video is a Hughes’ poem adapted for the smartphone generation. Both the song and video are one body of work which I have decided to analyse through the lens of what is known as the “double consciousness.” For social thinkers like W.E.B. Du Bois and Frantz Fanon, the belief in the internal struggle and social influence of the black identity is pivotal for surviving in society. For Du Bois and others, the fractured identity breeds conflict for people, especially for those of color, who strive to rise through society’s ranks. “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others,” Du Bois writes, which- along with Hughes’ poem- immediately came to mind during my first viewing of Gambino’s latest offering.

“This is America” is social dissonance you can dance to.

First and foremost, we have the opening scene which involves Gambino, shirtless, dancing over to a man playing a guitar, Clavin the Second (and not Trayvon Martin’s dad as the rumor mills started spinning), and firing a single round into his bag-covered head. This could symbolize the younger generation executing the older black artist; a reinforcement of the belief that today’s music needs to be amplified by gratuitous acts of of violence whereas the “back-in-the-day” more soulful variations just needed a guitar (aka real music).

This moment of shocking violence not only punctuates the start of the first verse, but it produces its first clashing visual image. The audience is lured into Gambino’s rhythmic dance moves and somewhat goofy facial expressions before being dumped right into one black artist executing another. Gambino then speaks directly into the camera and declares, “This is America/Don’t catch you slippin up” as if putting everyone on notice: this isn’t going to be your typical hip-hop video.

From there, the song weaves an odd tapestry of social commentary and trap beats. The murder weapon is escorted away by a youth who wraps it in a red cloth, a sign of reverence for the act, and the body is dragged away as Gambino bounces around and shimmies his way through the scenes.

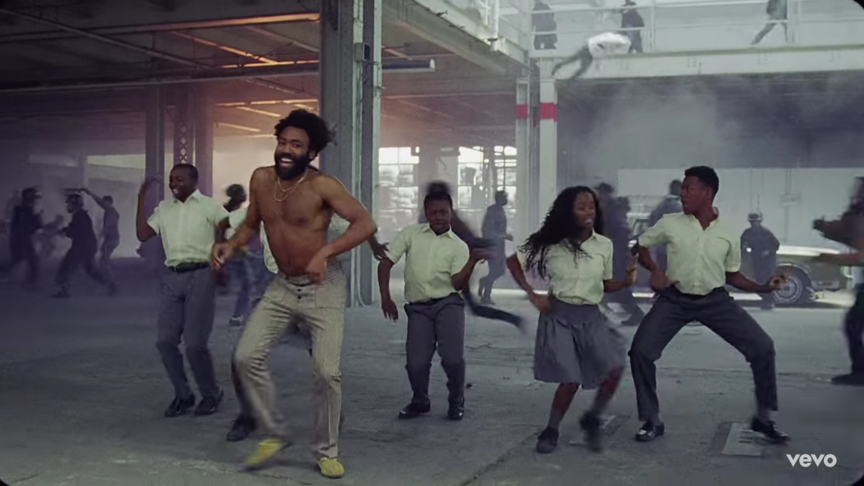

The kids return to dance along with him, each one smiling and heavily entertained. Though their moves synchronize with their idol and match some of the popular dances of today, they are dressed conservatively, call-backs to boys and girls in private institutions. They are adorned in uniform and matching choreography following the dancing black man they love as the world behind them is exploding with violence and chaos. Over this, Gambino raps:

Police be trippin’ now (woo)

Yeah, this is America (woo, ayy)

Guns in my area (word, my area)

I got the strap (ayy, ayy)

I gotta carry ’em

Of course this is said as Gambino keeps his distance from his adoring fans. When they rejoin him, his message changes entirely to the nonsense of your typical mumble rapper.

Yeah, yeah, I’m so cold like yeah (yeah)

I’m so dope like yeah (woo)

We gon’ blow like yeah (straight up, uh)

Behind their choreography, a young black man stands on an abandoned car firing a gun that is spouting money as others dance around him.Chickens group along the floor, a possible allusion black plantations. Meanwhile, Glover is carefully juggling his personalities here, expressing the burden of the black artist to be braggadocios and trendsetting while being the focal point of youthful escapism. But also, the image he portrays reveals so many layers. He is both bare, almost sexual and fetishized, while at times looking wild and aggressive with his movements and facial expressions. Glover oscillates between the two modes so smoothly that the audience isn’t sure which man they are going to get from one second to the next, the attractive icon or the violent aggressor.

This plays into the next stand-out scene which features a black choir chiming in:

You go tell somebody

Grandma told me

Get your money, Black man (get your money)

Get your money, Black man (get your money)

Gambino cartoonishly, almost jigs and jives, his way from the background to the fore only to pause and gun down the entire chorus. There’s a lot to parse through here. From a black artist once again “murdering” another black art style to a discussion of a black choir literally singing the praises of a black man, not for his spiritual enlightenment, but for his monetary gain.

There’s also the artist himself killing those that are backing his success. I’ll even drop in the allusion of the semi-automatic rifle and its significance not only in our current American culture, but also in the narrative of the African militant slaughtering those of a specific religious belief. And once again, the weapon is collected by a youth who drapes the gun in red.

Gambino curls back into arrogance and flash as the kids join him once more. Yet the world around them is even more chaotic. A body falls from the sky. A man in riot gear crosses their path.

I absolutely love the next shot which is a pan upward to a second level above the chaos. More youth are perched in its banisters, but their faces are all clothed. This could be either a reference to gang constructs in black communities or a bold representation of the Antifa movement. What’s stunning, either way, is how the youth are on their phones recording the revolution instead of taking part of it. This is, by far, a clever representation of a dual state of mind: an anti-establishment group only in garb and not in action.

The final image of the warehouse sequence is one of complete chaos. The kids are dancing by a burning car as a hooded man rides a white horse in the background (obvious allusions to race riots and slavery). They seem to be oblivious to everything around them until Gambino takes this pose.

At the sight of a black man holding a weapon, even with an empty hand, the song completely drops out and the kids scatter. What they find truly scary is the black body in a position of power. The scene closes on Gambino being left to dance on the scattered cars which have been abandoned, with cameos from the hooded guitarist at the start of the video and SZA looking on quietly from one of vehicles.

Of course, the final shot of the entire video begins with a pan upward from the warehouse and into darkness. Out of this, Gambino can be seen running towards the camera- an entire sequence that is shot almost like a deleted scene from Get Out (2017).

His smile his gone, his passion is thrown aside. All we see is a black man frightened and desperate. We then witness a faceless mob of people behind him, either attempting to chase him down or running out of fear themselves (or both).

This scene can be read as either Gambino seeing the result of his violent showmanship by becoming the target of a vicious society or, quite possibly, this can be a representation of the “double identity” This could be what is actually happening both mentally and spiritually in concert with his actions. The juxtaposition it poses is one in which it defines the black artist as someone who is using fame in order to survive in society while also running from society’s ability to swallow the black body whole due to its fame. It could also be possible that this scene, with its slow pan up into darkness for its transition, can be the space inside his head.

“This is America” is worth several viewings and well-worth all 34 million of its current views. I can’t recall the last video which has tried to manifest the cultural contradiction of the black experience in America (and that is far more than any current “college dropout” can boast about). Symbolically and philosophically, both the song and the video are tightly entwined to form a deeply riveting experience.

I am the young man, full of strength and hope,

Tangled in that ancient endless chain

Of profit, power, gain, of grab the land!

Of grab the gold! Of grab the ways of satisfying need!

When W.E.B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes speak through your craft, I don’t feel like there’s anything childish about it.

Alcy Leyva is a Bronx-born writer, teacher, and pizza enthusiast. He graduated from Hunter College with a B.A. in English (Creative Writing) and received an MFA in Fiction from The New School. Alcy enjoys writing personal essays, poetry, short fiction, book reviews, and film analysis, but is also content with practicing standing so still that he will someday slip through time and space. His first book “And Then There Were Crows” will be published July 3rd, 2018 by Black Spot Books. → Click here for more. ←