The first song I heard from The Walkmen was “The Rat” off 2004’s Bows + Arrows. It starts with this nerve-wrecking guitar chop and instantly puts the mind on high alert. Drummer Matt Barrick spits out tightening rounds on the hi-hat, bombing across the set again and again.

Hamilton Leithauser’s vocals swarm with frightening toughness and a scorched throat spitting out vulnerable lyrics. “When I used to go out I’d know everyone I saw / Now I go out alone if I go out at all,” he rips. “The Rat” is a song to crank on a night when things aren’t going your way. The song crests, erupts, then crests and erupts again. It leaves jagged cuts in the speakers demanding all the attention of the room.

“I’m sure we’ve been through this before / Can’t you hear me, I’m beating on your wall / Can’t you see me, I’m pounding on your door,” Liethauser shrills. He packs a tantrum into each sentence with shredded screams. Behind each yowl there is this heavy suppression of desperation, this erratic need for emotional payback. He’s the vocal equivalent of your bratty cousin who throws a fit whenever things don’t go his way.

“The Rat” is bitter, angry, and full of teeth-gritting emotion, but also steeped in self-doubt and loneliness. A lesser band would cut the vile determination for spite and turn it into some vapid punk rock song or an emo moper. The Walkmen’s music is structured to accurately reflect Leithauser’s ever-changing mood. They manage to sound both caustic and sensitive, pissed off but tear-stained, irrational but apologetic. Their music straddles the intensity of punk rock and the emotional output of indie rock, but careens into a space that is all their own. It’s never quite one thing, edging equally toward post-punk, Americana, folk-rock, and whatever else lies between.

The roots of The Walkmen sprout from Philadelphia, Washington D.C., and New York City. Hamilton Leithauser, Matt Barrick, Peter Bauer (on bass and organ), Paul Maroon (on guitar and piano) and Walter Martin (on organ and bass) formed the group in Manhattan at the turn of the century, and so were lumped into the emerging scene at the time–The Strokes, Interpol, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, TV On The Radio, Liars–among others.

Back when computers were bulky and anchored to the home’s “computer room,” I downloaded “The Rat” and a few other songs off KaZaA, the long-gone pale white and lime green peer-to-peer music service–with dial-up. When it would take days to get one full song. Days.

The name was promising. The Walkmen. In the style of both the recent crop of indie stars, as well as the early rock bands of the 50’s and 60’s, the name was a wink and nod to the musical past that would be ever-present in their musical DNA. It’s also a tongue-in-cheek send-up to the old hand-held cassette players–the memory of which was fading fast with each percentage point notched during my long download.

I immediately fell in love with their raw and wounded rock-and-roll. They were always a step away from the coolness of the other bands–not as debauched and careless as The Strokes, not as mysterious and aloof as Interpol. The Walkmen leaned more toward the hardscrabble reality of the Average Everyday, the monotony of forgettable afternoons, the crippling effect of boredom and heartbreak.

Their music is full of tough sorrow, the type of sadness that creeps in the shadows of a leather jacket and a hidden flask of whiskey. Liethauser doesn’t hide his regrets, he puts them front and center and barks right at them, mocks them a little.

The Walkmen sound reaches across the generational divide. They follow the regular paradigm of rock music: drums, guitar, bass, heart-shredding vocals. But with that, they add a swirl of circus percussion, jingle bells, old-timey saloon-style piano, sprawling organ and drums that smoke and burn out. As much as they might seem like a current day revivalist act, their sound can stump the listener into thinking they’re some undiscovered gem from the Appalachians at the end of the last century, or a swilling bar band in New Orleans from decades past. There is no finger on it you can place.

Their first full-length album Everyone Who Pretended To Love Me Is Gone was released in 2002. Right away they realized their sound. Maroon’s lazy jangling guitars do the tango with skittering piano notes; Barrick’s cascading drums circle the many jingle bells jingling on “Wake Up,” “The Blizzard of ’96,” and “We’ve Been Had,” some of the album’s best songs. The album is loose and discordant with lo-fi leanings and Leithauser stringing everything together.

Two years later they released their second breakthrough album, Bows + Arrows, featuring the aforementioned “The Rat” as the lead-in single. “Hang On, Siobhan” is a lazy after-hours waltz over twinkling piano keys. “Hang on,” Leithauser cries, holding the weight of a long lonely night in each sobering note.

The music of The Walkmen really started to chisel a home in my head when I first visited the East Coast; Boston. It was 2006. May. Their third album, A Hundred Miles Off had just been released. Right down to its title, the album is perfect for the road. It’s easy-going, dry and coated with horns rusted by the sun.

The spring freshness–that relucent dew–itrushed in and out with each breath. I sat on a dark red bench with the Charles River slushing before me, smoking cigarettes, feeling woozy, and listened many times to A Hundred Miles Off as the sky turned darker shades and left me with an adhesive film of sweat stuck to my skin.

The album is more laid back in tone than the previous two. It’s perfect for wandering under bridges and through public parks in range of the springtime sun. The streets in Boston are cobble-stoned, entrapping, and shrouded by trees that overhang and brush the back of your neck as you pass. They lead into knotted intersections and unknown alleyways and many times you might find yourself far from where it was you thought you were.

When “Lost In Boston” came on during these directionless moments my face eased with a smile at the casual irony. “Lost in Boston drinking rum and chocolate / A hundred thousand blinking lights are making me exhausted,” Leithauser sings with that clunky rhyme scheme. The song became an anthem for my wayward existence. When I hear it now, I see Massachusetts Avenue before me and can feel the near-dizzy tobacco lift launched by a hundred dangling cigarettes.

Over the course of The Walkmen’s discography Leithauser’s inner angst starts to meter out into melancholia, and then finally into remission and complacency. Their final three proper albums, released every other year starting in 2008–You & Me, Lisbon, and Heaven--offer the world the definitive, refined sound of The Walkmen. Any of these three albums could be presented as the group’s best. They are records with an awareness of the bigger picture. They work through the throes of adulthood and family life and look back at the trials and tribulations that brought them to their current standing.

“I was the Duke of Earl but it didn’t last / I was the Pony Express, but I ran out of gas,” bellows Leithauser on the opening track of Heaven, “We Can’t Be Beat.” White flags are raised. The crowds have gone home. Leithauser isn’t seeking revenge anymore, only the comforts of home and a piece of solitude after the smoke clears. “Back to school / Back to work / Can this go on forever? / Angela / What’s the difference? / Life goes on all around you,” he sings with equal detachment and acceptance on “Angela Surf City” off Lisbon.

After living for a number of years in Massachusetts, I leapt and landed in Manhattan, uptown, about twenty blocks from where The Walkmen first started their recorded existence: somewhere near 138th Street in Harlem, in the now-defunct Marcata Recording studio. (The engineer Kevin McMahon has since moved the studio to Upstate New York.) Fifteen years ago Maroon, Martin, and Barrick–then in the band Jonathan Fire*Eater–built the studio. A year later they would join Bauer and Leithauser, who were playing in The Recoys, and form The Walkmen.

Their debut, self-titled EP and first three albums were recorded there. “Pussy Cats” Starring The Walkmen, a note for note re-recording of the classic Harry Nilsson album, was a tribute to the studio, before they were evicted.

Walking down dark Broadway Avenue now I listen to “The Rat” and feel the distressed grip of each note. Ten years later the song still gives me the chills like it did when I first heard it.

“We have no future plans whatsoever,” Bauer told The Washington Post last November. “I’d call it a pretty extreme hiatus.” It wasn’t a red line, but the offhandedness of the statement makes it feel this may be all we get of The Walkmen.

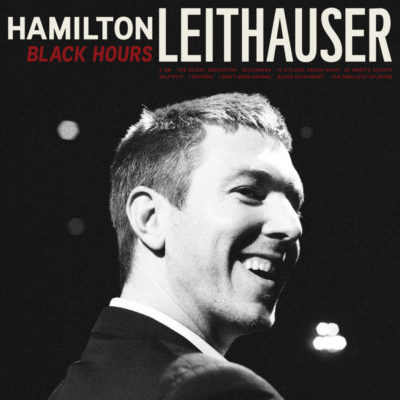

They are all free agents. Three members are pursuing solo careers, jumping at the chance to stand at the helm giving input and direction. Leithauser released Black Hours in June, Bauer just put out Liberation! (as Peter Matthew Bauer), and Walter Martin recorded We’re All Young Together with some members of the Walkmen, Yeah Yeah Yeahs and the National.

The word “hiatus” leaves open the hope that they may return to the stage at some point in some undefined future. Fingers are crossed. If it never does happen though, The Walkmen leave us with a fourteen-year discography–six full-length albums, one Harry Nilsson reboot, several EPs–to carry through life’s many wide and deviating curves.

Born in Arizona, Eli Jace left the desert on a whim for Boston and wound up following the covered up and detoured paths of journalism. He doesn’t know how this happened. He’s written for The Berkshire Eagle and Somerville Scout before moving to New York City. He works for the New York Post and writes for Independent Music Promotions and Quiet Lunch.