Warning: by reading this article you will expand your vocabulary and learn about neuroscience -I know I did when I wrote it! Should you find yourself in doubt when reading, please check the links. Enjoy!

“There are things known and there are things unknown, and in between are the doors of perception.” –Aldous Huxley

It’s a chilly mid-April afternoon in Brooklyn and the sky over Greenpoint is slate grey. I resolve not to let the cold wind tousling my hair (and messing up my do) or the gloomy atmosphere dampen my excitement for my imminent studio visit with artist Jean Pierre Roy. As my friend and artist Larissa De Jesus, who is accompanying me today to photograph the interview, says, “If you haven’t’ heard of Jean Pierre Roy you must have been living under a rock!” Her statement is true; over the past few months, after his acclaimed participation at Volta within the 2018 Armory Show, Roy’s name has been popping up on countless articles on line and print. The Brooklyn-based artist has been unanimously praised by the press and hailed as one of Leonardo di Caprio’s favorite artists (Di Caprio snapped up Roy’s painting Landscape with Divergent Perceptual Reference Frames (2017) during Volta’s opening hours). The correlation between the movie star and Roy does not feel far-fetched when you meet Jean Pierre in person. Standing at 6’3”, charming and friendly in a warm, welcoming way, Mr. Roy has rock star charisma.

The artist welcomes us in his studio in Greenpoint, within a large industrial brick building complex. I look around and the only artworks I see are lots of small-scale preparatory sketches, carefully hung next to each other on a large white wall. Jean Pierre smiles a large grin and immediately excuses himself for the bareness of its walls (his paintings are in high demand at the moment). However, I find it exciting, as it gives me the opportunity to get a glimpse of the artist’s inner sanctum without the diversion of his “epic orchestrations,” the way I like to describe his complex, dynamic, hyper-realistic tableaux. Roy’s studio is spacious and bears the telltale marks of an artist who spends a lot of time in it. In the main room, there is a workout bench with heavy weights and a thick climbing rope hanging from the celling in one corner. In the next corner hangs a dart set. “After many hours spent working in here I get restless at times, hence the exercise equipment… I also need to give my friends a good reason to come and see me and hang out,” the artist says jokingly, gesturing towards the dart set. I begin to imagine Jean Pierre spending long hours in his studio, concentrating on the complex task of portraying realistic yet surreal, metaphysical scenarios. When looking at the artist’s colorful, detailed depictions of post-apocalyptic landscapes, populated by featureless individuals engrossed in Sisyphean tasks, the viewer perceives that the artist is trying to tell the story of an inner struggle, to investigate the limits of perception. I am brought back from my reveries by Jean Pierre who invites us to take a seat in the office within his studio. The space is filled with many shelves of books, photos, even an old school turntable and record collection, and, on the main wall, a series of many small self portraits, the artist’s Negentropic Project (explained and illustrated in detail in the Vimeo video in this article).

EZ– Are your paintings allegories? Is there a message or warning in them?

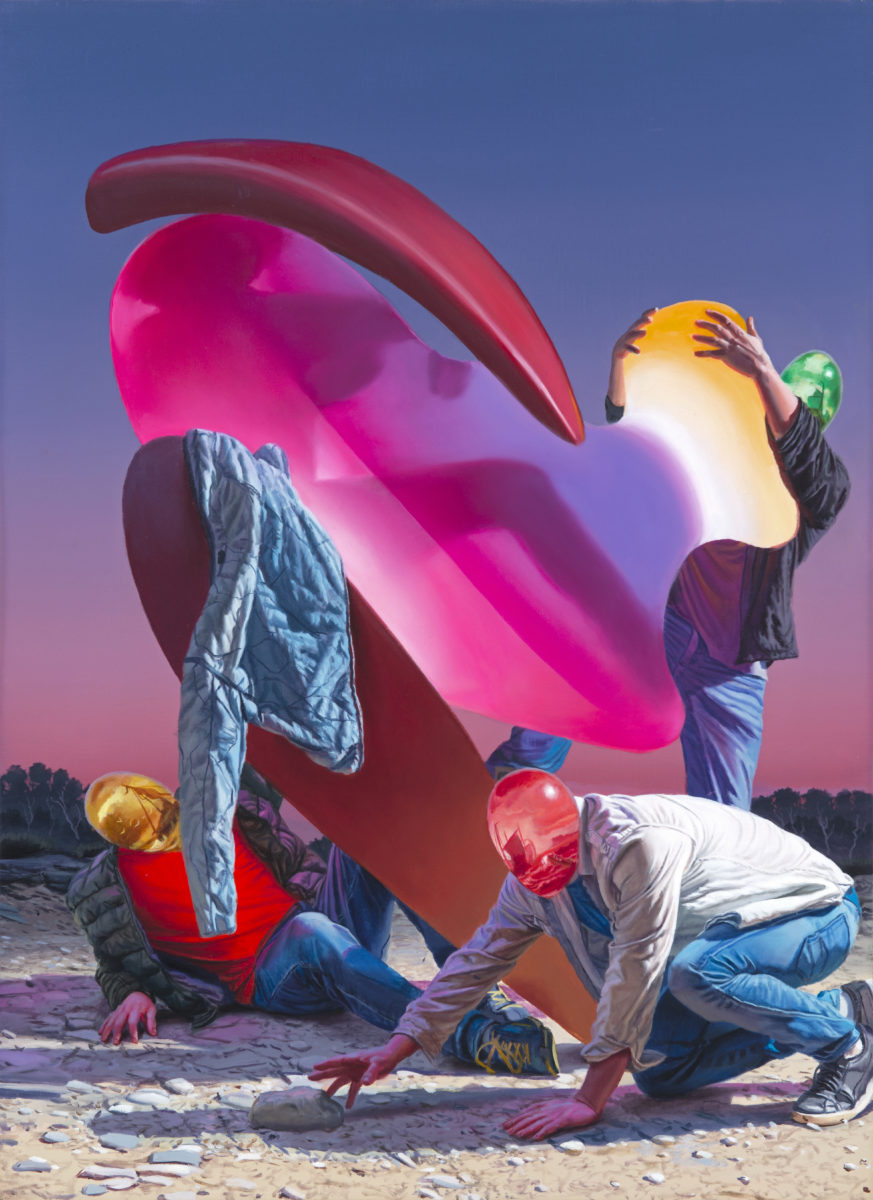

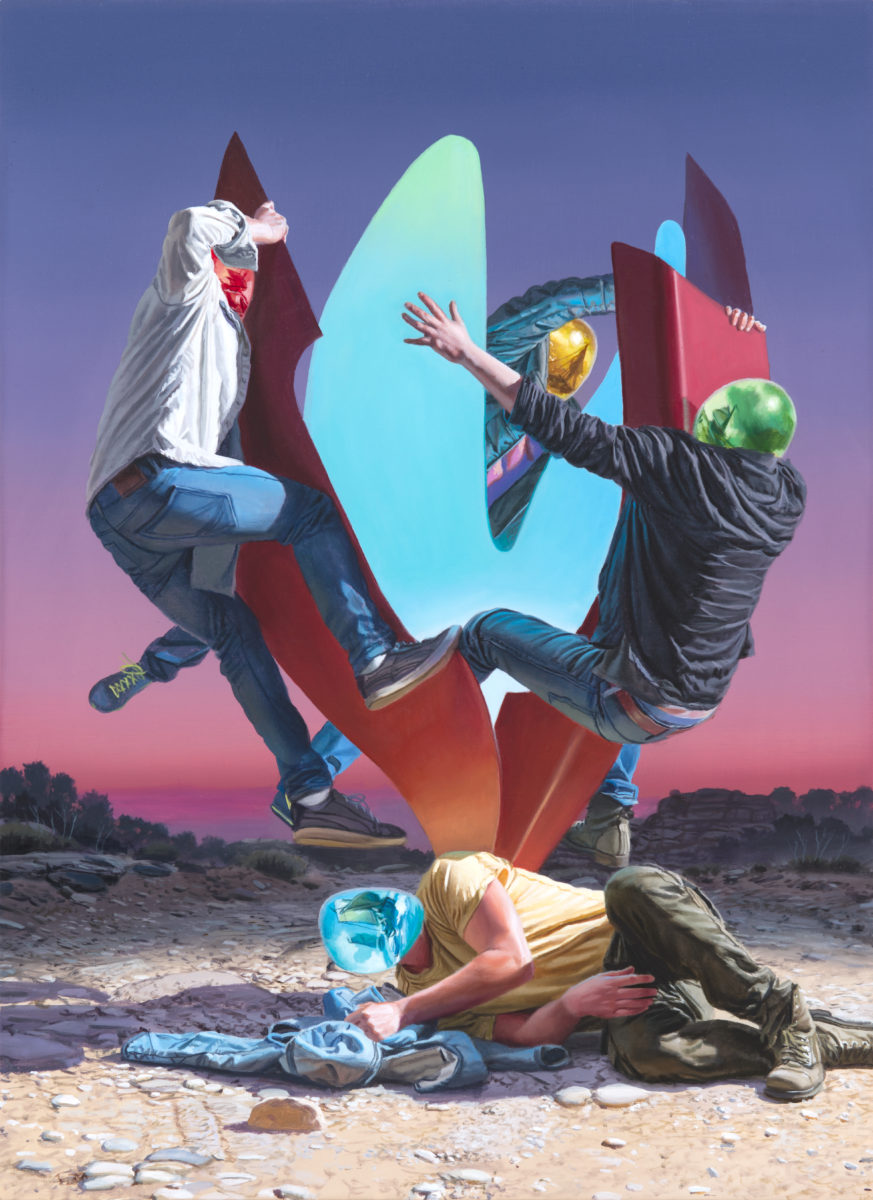

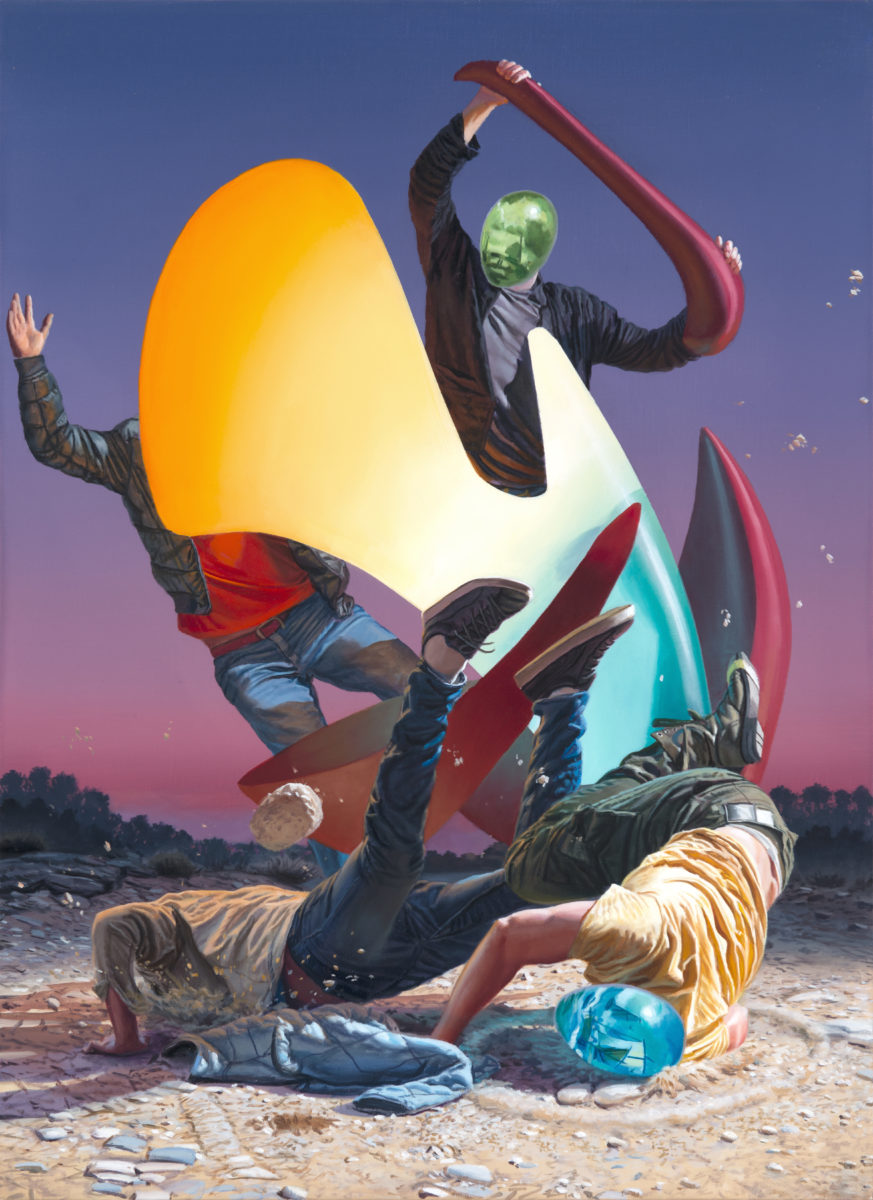

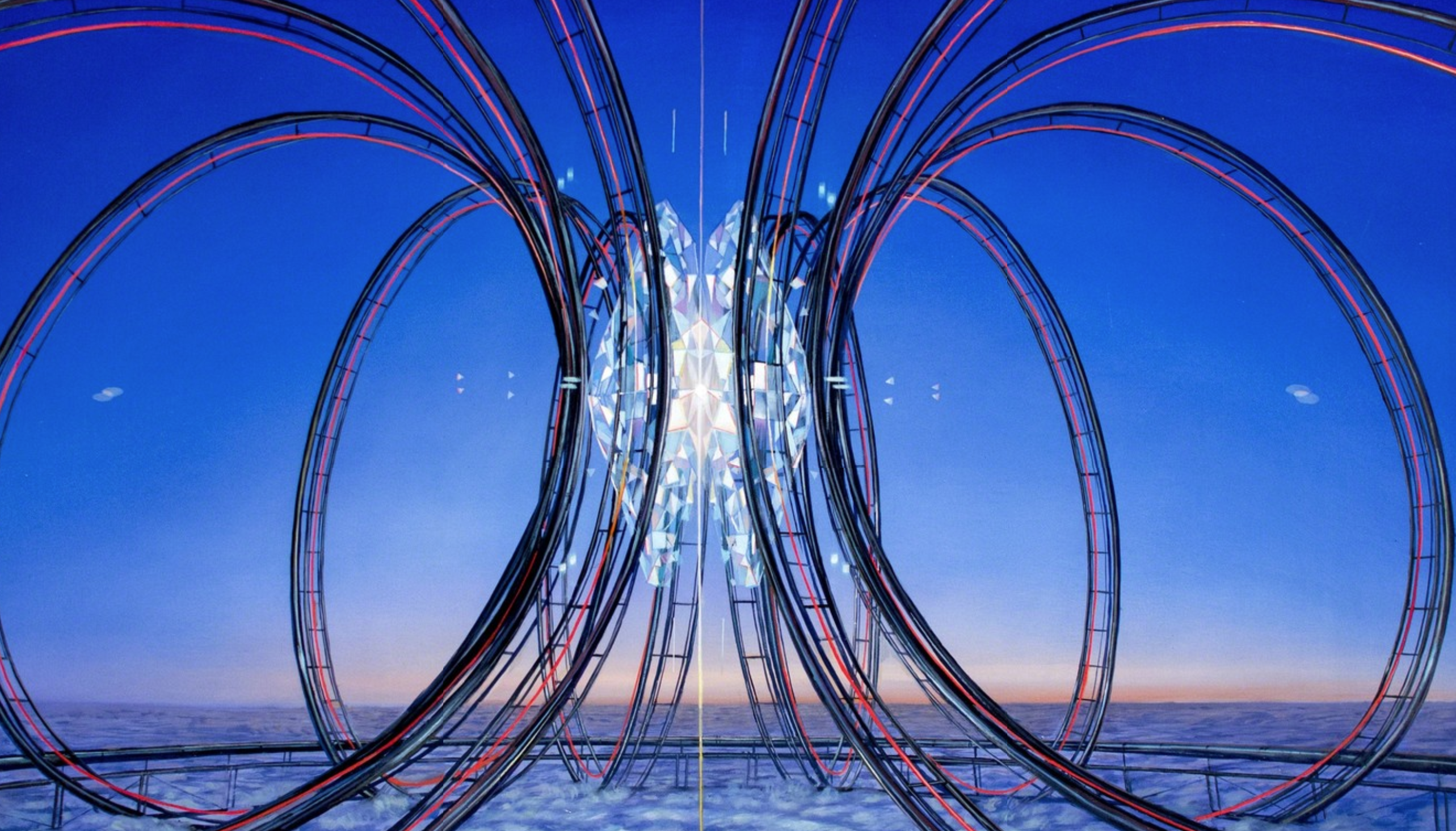

JPR– My recent work, Aporetic Sequence, comes from wanting to pictorialize a very specific feeling: the moment when a perceptual image slips from one’s cognitive grasp. Reality, as we perceive it, is a construction. It is shaped and framed by our cognitive biases and the specificity of our personal neurological wiring. The interpretation of sensed information is specific to the state of the consciousness that perceives it. While robust and historically effective, our biological systems for perception and cognition evolved for an environment that no longer exists. The arrival of the Anthropocene challenges these finely tuned sensory systems on a daily basis in a myriad of ways, but which can rather simply be summed up by the heuristic saying, “Our ability to create change in the world is greater than our ability to perceive and understand that change.” This feeling of an impasse, this state of Aporia, is like any other feeling on the surface, in that you only really know what it feels like when you are feeling it. It is a slippery, charged, and capricious feeling, like grabbing at a slow floating piece of dust in the air, only to have it race out of your grip at the last moment, propelled by the very force of your hand acting on the air that carries it aloft. These series of 9 loosely sequential paintings chart the self-contained narrative course of 4 figures as they literally grapple with the ungraspable. The self-illuminant non-spatiotemporal geometry—representing an aporetic impasse—shifts and slips from the figures’ hold as they wrestle with the form and themselves.

EZ– Given its methodical attention to detail, your latest work has been recently described as hyperrealist and neo-surrealist. However, when I saw your paintings at Volta, Italian Baroque masters and the 16th century Venetian School came to mind. Who are the artists who inspire you the most and why?

JPR– That is a long list that has evolved so much over time, but inclusion in it is often tied to watershed moments in technical or conceptual growth. Like a lot of artists born in the 70s, I grew up looking at some incredible illustration and learned much of my foundational visual language from them. Mobieus, Milo Manara, Syd Meade, Ralph MacQuarrie, Ron Cobb, Hugh Ferris, Richard Corben, and Kevin O’Neill founded the basis of my visual memory because comics and film were a lot more accessible than galleries and museums to a 14 year old. It wasn’t until later when I began studying art in earnest that I found their predecessors. My work has become a weird mix of the dynamic, direct light and figure driven narrative of the 16th century Southern European painters (Ribera, Barocci, Veronese) but with the slavish, obsessive focus on material specificity and poetic micro-articulation of the Northern European painters (Metsu, Holbein, Dou.) It’s a strange synthesis, but it allows me to bounce back and forth between articulation and obfuscation in the same image.

EZ-Although your artistic output has been recently defined as “far-out sci-fi painting,” I see a lot of mythology in your art (think of taurokathapsia or bull leaping in Minoan friezes). In your latest series “Aporetic Sequence”, the protagonists are twisting, jumping, or getting thrown to the ground. Are they intended to be Gods or humans?

JPR– Painting in a representational language comes from two primary places for me; First, it is a compulsion—working with form and trying to capture light, chroma, and volume that describes the optical world in a familiar way is the only way that I’m really comfortable. Second, it allows me to participate in art’s long and complicated relationship with the history of the study of perception. Before Newton, many artists in their studios undertook the study of “seeing” (after the Greeks of course). But following the codification of “Optics” into a scientific discipline, the study of seeing became less and less about the mechanics of “world out there” and more about the neurological structure of brain and how it interprets information. In stark contrast to DaVinci’s hydrodynamic studies, Vermeer’s laser-like clarity, or the color-field obsessions of 20th century artists, 21st century investigations in the nature of perception tend to be non-visual. This doesn’t mean, however, that they lack a strong emotional narrative. Cognitive biases, neuro – perceptual blind spots -the freedom with which the mind can “fill in the gaps”- and invent visual information out of nothing, can leave the individual with the feeling that the “objective” world is slipping away from them. It is that feeling that I wanted to create a picture about, though one that is inherently non-visual. The “Aporetic Sequence” is visual, narrative construction that tries to pictorialize the Qualia of that feeling. The twisting, the wrestling, the getting-thrown-to-the ground, is all an attempt to capture the feeling of our capricious relationship with perception, and its inability to be corralled into solid form.

EZ– You’ve said “I have always been obsessed with the reductive investigation of natural systems and their visual replication.” Can you explain this statement little more in detail?

JPR– There isn’t a single major challenge that we face as a culture, a species, or a planet that doesn’t require some level of scientific literacy. In trying to solve those problems, we cannot have any predictive interaction with the forces of any given system without a thorough understanding of all the forces at work within that given system. The mechanics of reality can be deeply, deeply counter-intuitive once you get beyond a certain level of complexity. Working representationally is a way for me to indirectly participate in the study of the natural world, or at least keep up to date with the state of the literature. Breaking meteorological and geological system down into abstract patterns allows me to literally build worlds back up into an emergent, representational system from a few sets of abstract mark-making rules. Clouds have different shapes based on the amount of heat and moisture in the air, veins of rock poking through snow or grass share angular direction and stratification. When you paint a landscape you’re accounting for millions of years of non-visible forces that extend way outside of the space-time represented within the four corners of the picture plane.

EZ– William Blake said, “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite.” In describing your art, you talked about “The Suspension of the Known. That which lies between what we have seen, and what we know must be there, but can never reach, the yearning for the immaterial.” Are the subjects of your paintings on a sort of a shamanistic quest to grasp a glimpse of the “unknown”? Are those amorphous, twisting, iridescent shapes in your “Aporetic Sequences” rips in space-time continuum? Or William Blake’s “doors of perception”?

JPR– Anytime someone uses a phrase like “rips in the space-time continuum” in reference to one of my paintings, I feel like I’m doing my job well. There is a ton of bad science fiction out there, but the good stuff lets you know up front that your presumptions about the nature of reality will be questioned, and often turned inside out. I’m less and less drawn to the escapist tropes of the genre like lasers and space battles, but I love the metaphor of technology carrying the audience over the horizon of self-discovery and revelation. When I was a kid, my father drove me up to Vandenberg Air Force base in California to see the Space Shuttle sitting on the launch platform before they moved it to Florida for launches. That giant, white, and earthy red machine literally joined the flat plane of the finite human world with the infinite dome of the beyond. It was a figurative and literal extension of the human sensory-perceptual model. We build a tool to extend the reach of our perceptual doorway just a bit wider out into the void. In a way, I’ve been chasing that feeling ever since. The “Aporetic Sequence” began from the desire to want to pictorialize the deep desire to catch reality revealing its shape, while knowing that by definition, the human perceptual model is cut off from any “objective” reality. But just because something is unachievable, doesn’t mean it’s unapproachable. The figures in the sequence are trapped in struggle with trying to internalize the external—the moment when the act of bringing something from abstraction into clarity breaks down and realization slips from your cognitive grasp.

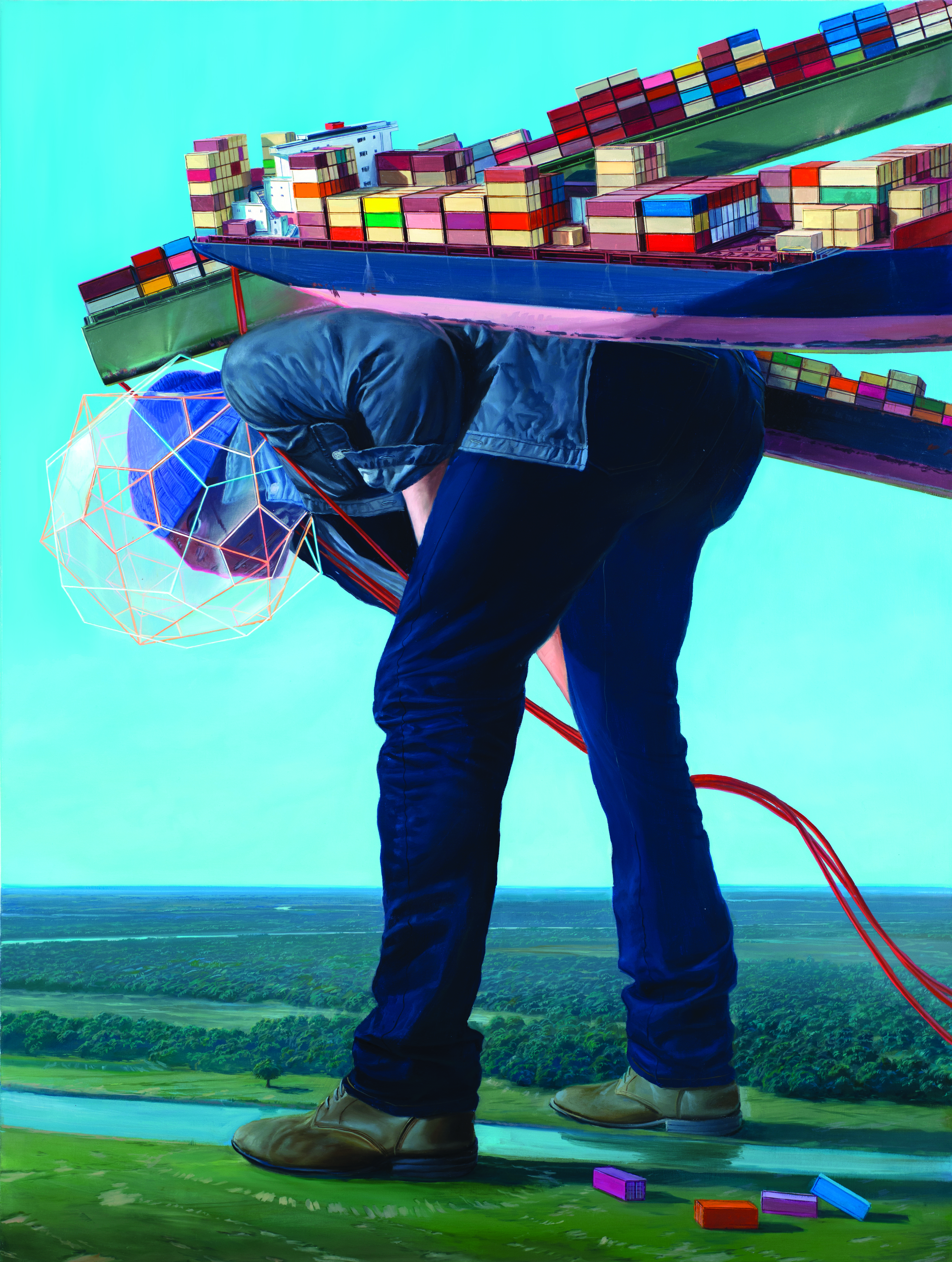

EZ– You transitioned from hauntingly beautiful, post-apocalyptic landscapes (your “Homecomings” series and “Zero Hours” series), to introducing buildings in ruins and wreckages in your compositions as in your series “First Eyes on the World.” Only later, in your “A Rational Spectacle” and “Terraformer” series, you introduced the human element: self portraits as a giant, as if you were “the last man on earth.” Could you tell me more about your early choice of not portraying objects or biological organisms in your dystopian landscapes? Is your one gigantic protagonist of your “Terraformer” series depicted in the act of modifying its environment or creating it, a sort of neo-demiurge?

JPR– I received my MFA from the New York Academy of Art, a figurative-focused program. While there, I was awarded an anatomy residency in Oxford where I worked with cadavers in a dissection lab for a summer. The intimate experience of working with the bodies of the deceased and how loaded the language of the body was, even after death, made me realize that I didn’t want to include figures in my paintings unless I had a really, really good and specific reason to. One of the inherent problems with studying how to paint by using the figure is that it is easy to confuse the process for content. I knew I didn’t want to arbitrarily include the figure in my early paintings simply because I was used to putting them in there to complete a project. The other factor was that I moved to NYC 3 weeks before 9-11. I saw both planes hit and both buildings fall. Not to gloss over the lasting impact of that event on myself and the world, but the sheer scale and spectacle of that event left me enough to process for years without needing human-scaled objects. As my work developed, particularly around the “Terrafomer” show, I had about ten years of literal world-building behind me, so Neo-Demiurge is a great term for what I was feeling. I was really drawn to Goya’s use of the Colossus as a metaphor for the existential terror of the world unmaking itself in the face of the chaos of war and national collapse. But for me, with all of this knowledge acquisition and no apparent outlet that might serve the immense global challenges facing us, I wanted to appropriate the all-powerful giant and recast him for the Anthropocene. With humans having a bigger impact on the planet than the forces of nature itself, the Colossus became this impotent world-builder—all the power, none of the predictive vision. From there it evolved into an autobiographical construct that tracked my interest in studying inherently non-visual systems of the neuroscience of perception. How do to groups of people take in the same perceptual information and weigh it in radically different ways, producing drastically different internal models of reality? The painting slowly became less about the literal, apocalyptic grammar of dystopian allegory, and more about an attempt to externalize the internal battles of the cognitive biases and perceptual blind spots that keep us from seeing the world as it is “in and of itself.”

Jean Pierre and I continued to talk for a long time, as he was full of insights about art and human perceptions of reality. Due to the lengthiness of our conversation, many of his remarks could not be included here but it was a pleasure to have the opportunity to speak with him and look at the world through his eyes.

Neuroscientist Patrick Cavanagh, director of the Vision Sciences Laboratory of Harvard University’s Department of Psychology, believes that “artists are the original neuroscientists.” Jean Pierre Roy is a master of representational art, yet he strives to paint the unseen, channeling his curiosity about human visual perception into an artistic study, scrutinizing the liminal area between art and science. His works are a study of the principles of visual cognition, a psychedelic voyage into the mystery of the physics of the human perceptual mechanism.

The next time you will come across one of Jean Pierre Roy’s mesmerizing paintings, remember it’s not about what you see, but what you can’t.

Jean Pierre Roy’s upcoming exhibitions:

At 601 ArtSpace, 88 Eldridge St. NY, NY 10002- Group Show – opening June 14ht, 2018

At Gallery Poulsen‘s Summer Show, in Copenhagen, Denmark – opening August 11th, 2018

Jean-Pierre Roy: ”Aporetic Sequence 6” 2018, oil on linen, 56 x 41 cm, 22 x 16 in

Jean-Pierre Roy: ”Aporetic Sequence 9” 2018, oil on linen, 56 x 41 cm, 22 x 16 in

Jean-Pierre Roy: ”Aporetic Sequence 8” 2018, oil on linen, 56 x 41 cm, 22 x 16 in

Jean-Pierre Roy: ”Aporetic Sequence 3” 2018, oil on linen, 56 x 41 cm, 22 x 16 in

Jean Pierre Roy in his studio in Brooklyn, April 2018, photo by Larissa De Jesus

Jean Pierre Roy in his studio in Brooklyn, April 2018, photo by Larissa De Jesus

Jean Pierre Roy and Eva Zanardi, April 2018, photo by Larissa De Jesus

Video by Larissa De Jesus

EARLIER WORKS

Jean Pierre Roy, “Sight Specific”, 70” x 108”, oil on canvas, 2009.

Jean Pierre Roy, “No Treasure But In Them”, 2014, oil on canvas 152 x 112 cm

Jean Pierre Roy, “The End of the Old Model (λ 660”) 72” x 60”, oil on canvas, 2008.

Jean Pierre Roy, “Levitating Mass”, 2013 , oil on canvas 122 x 107 cm

Jean Pierre Roy, “Parade of the Blind Traveler”, 92 x 98 cm, oil on canvas, 2007

Jean Pierre Roy, “Shore For The Unmanned”, oil on canvas, 102 x 76 cm, 2014.

Jean Pierre Roy, “Light Not Heat”, 2013, oil on canvas 56 x 91 cm

Jean-Pierre Roy, “Macroherence”, Oil on Canvas, 180 cm x 152 cm, 2014

Jean-Pierre Roy, “The Participants”, 2016 Oil on linen, 55 × 75 in; 139.7 × 190.5 cm

Jean-Pierre Roy , “Scope For All Directions”, oil on canvas, 61 x 50 cm, 2014.

Jean Pierre Roy in his studio in Brooklyn

JEAN-PIERRE ROY

Born 1974, Santa Monica, California

Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York

Jean Pierre Roy CV

Jean Pierre Roy Website

Eva Zanardi is a curator, art advisor and art writer specializing in Kinetic Art, Op Art and Minimalism. She curates a contemporary art blog, “The Responsive I“.