They used to call Chicago the Jewel of the Prairie.

I call it a small blue island in a vast sea of red. Not that that’s a good thing.

Sometimes we’re the Windy City, for either the politics or the meteorology. Other times we’re Second City, for either our centuries-old phallic competition with New York City or how we rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1871 (caused either by a cow or a lightning strike, but never both). And either way, we’re stuck in the middle of the country, halfway between the east, home of the most important city in the world; and the west, home to the most self-important city in the world.

Chicago’s reputation is one of violence (from Capone to Chiraq); of meatpacking and big shoulders (Sandberg); to hard work and hard-boiled politics (Daley, Emanuel, etc.). And even though these narratives don’t usually put Chicago at center stage for the mainstream story of modern culture, we’re okay with being the outsider. We can get more done that way.

Plus, it’s outside the mainstream of modern culture where the story actually happens. That’s the story I’m interested in telling here at Quiet Lunch. As any writer knows, what you don’t say is usually more important than what you do. And when it comes to culture—and however it’s defined (with the sound of whoever’s voice and support of whatever’s institutions and investments)—there’s a lot that isn’t said. So what better place than Chicago to start saying it?

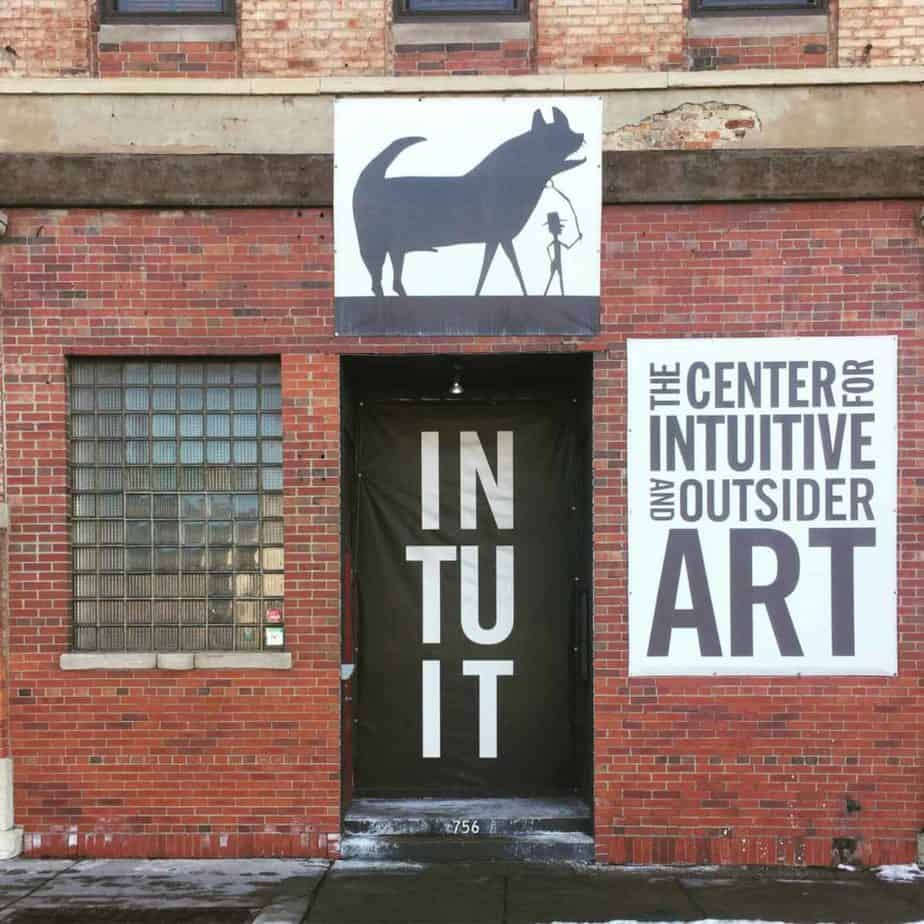

Chicago agrees. After all, it’s home to the only nonprofit in the world exclusively dedicated to the promotion and exhibition of outsider art. Better known as Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.

Inside Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art

Founded in 1991 and located in an unassuming storefront gallery space at 756 N. Milwaukee Avenue, Intuit is focused on the “work of artists who demonstrate little influence from the mainstream art world and who instead are motivated by their unique personal visions (e.g. art brut, non-traditional folk art, self-taught art, and visionary art).”

In addition to a rotating cycle of exhibitions, events and programming, Intuit is also home to a permanent collection of works by Henry Darger, the hospital custodian, recluse, and posthumously famous poster-boy of outsider art, known for his 15,145-page fantasy manuscript, The Story of the Vivian Girls, and reams of associated illustrations and watercolor paintings (all expertly memorialized in Jessica Yu’s 2004 documentary, In the Realms of the Unreal).

When I visited Intuit for the first time in January 2018, they were exhibiting the works of Eddie Owens Martin (1908 – 1986), better known as St. EOM and the creator of Pasaquan, a seven-acre “art environment” located near the town of Buena Vista in western Georgia. With its six built structures and nearly 1,000 feet of painted masonry fences, totems, walkways, sculptures, and artificats, Pasaquan has its own preservation society and stands on the National Register of Historic Places, with funding from the Kohler Foundation – but not even these posthumous accomplishments have yet been enough to land St. EOM a Wikipedia page (though Bomb Magazine gave his career an excellent write-up in this April 1987 profile).

Textiles and works by St. EOM

Beyond its current life as a roadside attraction, Pasaquan is also the name of a future world and home to the creatures that visited St. EOM when he was sick with a fever. The beings told him to move back to his home state of Georgia, where he ran away from in 1914 to go to New York City to pursue the Bohemian dream of being a waiter, bartender, dancer, prostitute, drag, pimp and gambler. After a storied life spent in the city and on the open sea, the “humanoid” entities endowed St. EOM with a utopian commission to create the preeminent psychedelic temple from the future.

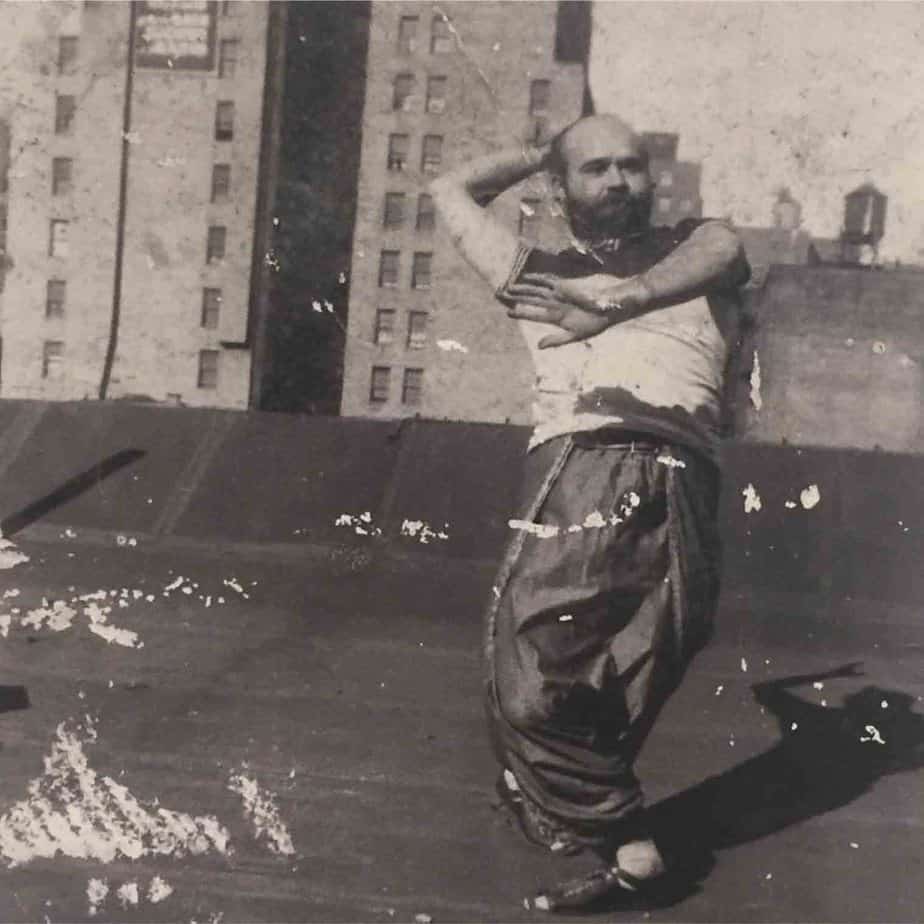

The Intuit exhibit of St. EOM featured original paintings, jewelry, textiles and sculptures of his work dating back to his New York years, where his eccentricities—turban, beard, and all—were first memorialized in ink by the then-year-old Village Voice as “one of the most colorful registrants” in a sidewalk art show at Washington Square. He was living in St. James Hotel at the time, and told the Voice that he was exhibiting as not as Ed Martin, but as St. EOM, adding: “I’m showing jewelry this year, as a change from paintings, but I’m really a fortune teller.”

St. EOM

St. EOM’s work is intensely holistic and hallucinatory. There are anti-gravity “Power Suits,” which will make you weightless if worn properly. Handmade jewelry; crude but compelling. An aggregate aesthetic fractious with the broader art community and, eventually, stuck in the sweltering woods of Marion County like a polychromatic fly in the ointment of local plantation culture.

Like most other artists featured by Intuit and recognized in the broader world of outsider art, to whatever extent that’s a sensible concept, St. EOM also belies a deep, psychic introspection. Notes of fever dreams, future visions and metaphysical sciences underscore the entirety of art works. Their pervasive idiosyncrasy was and is anachronistic, not only with the artistic trends of his contemporaries, but also with the aesthetic and spiritual dogmatics of mainstream culture. Even today his work stands out as peculiar, compelling, and unsettling. Sort of like watching a slow-motion car accident happen in the sixth dimension.

In other words, St. EOM, and outsider art in general, has an occult appeal. Not in the pagan, pantheistic sense of the term, but literally and etymologically; occult as the relative of occluded; the closed-off, obstructed, hidden, and blocked. Occult knowledge is secret knowledge. St. EOM’s art was reflective of his secret esotericism, or what Intuit calls “unique personal vision” (a subtly Nietzschean bit of marketing lingo). What is outside is what is secret—something intuitive and precognitive.

But as we can see with Intuit and it’s funders, outsider art has enough substance to officially exist as a cultural and artistic category. On one hand, this reification runs contrary to the genetics of outsider art as a form of privileged knowledge, but on the other hand, the occult secret is preserved, because it is not and cannot be concerned with defending its own appeal in linear terms (which is to say, mainstream logic). You either get it or you don’t.

Outsider art is what isn’t being said. Sometimes you can hear it, often as a shadow of its original instantiation or incarnation, as at a posthumous exhibition at a storefront gallery in Chicago. But usually it’s hidden, happening at the periphery, in the moment, and without concern for dialogue or profit. In other words, “outside” is as much an attitudinal aesthetic as it is a cultural ethos.

Intuit hosts In the Land of Pasaquan: The Story of Eddie Owens Martin from Dec. 22, 2017 to March 11, 2018.

* * *

Side note: This is my first-ever article for Quiet Lunch in a new series I’m calling “Outside Art.” Compared to the usual culture-media pipeline, I’m not writing this series from New York City or L.A., but from my home city of Chicago.

With this series on outside art, I’ll continue exploring the cacophonic sounds, conflicting visions and crude manifestations of occluded culture, past and present. This applies just as much to the identity politics of America’s flyover country (and its capital cities) as it does to the economic and intellectual ebbs and flows of pop-culture dialectics.

I welcome your questions, critiques, recommendations and incantations as we learn if some things are better left unsaid. benvanloon01@gmail.com